Escudo

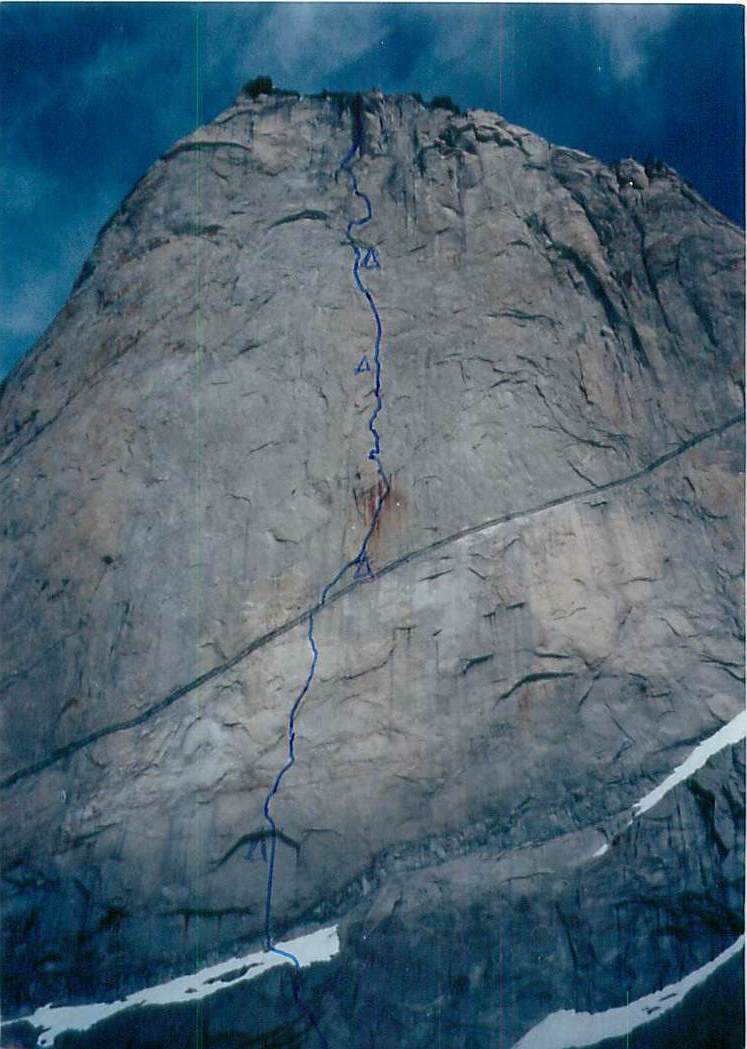

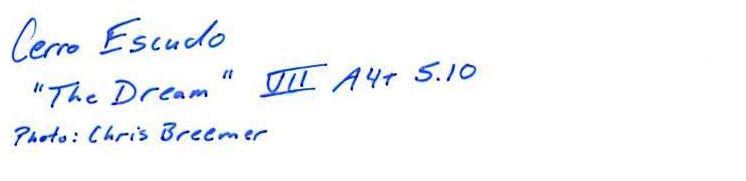

In 1994, the 4000 foot East Face of Escudo in the Torre de Paine group in Patagonia got climbed by Brad Jarrett, Christian Santelices, and Chris Breemer.

John MIddendorf had explored the area in 1992 with his girlfriend at the time, and had shared the photo of the unclimbed face with Brad Jarret. The original 1992 photo is shown below:

Also around that time, John Middendorf had also recently developed the first “Diamond Ledge” created specifically for situations where severe winds were encountered (wind travels up walls!). It had a structurally reinforced fly (webbing suspensions) on top and bottom to enable vertically opposed anchoring to counteract the severe winds found in Patagonia (it had the added bonus of allowing a third team member to bivy in the lower compartment). John had developed the Diamond Ledge for a 1993 attempt on the East Face of Cerro Torre, but his partner had declined to attempt it (instead they did the Compressor Route). But the following year, John was happy to share the new technology with Brad and his team. Their successful ascent was really the first time a major big wall style climb had been done in Patagonia without recourse to extensive fixed ropes. This is called “Alpine Style Big Wall Climbing” where there is no safety tether to the ground and involves much higher levels of commitment.

Below is the report from the 1995 AAJ:

Escudo, East Face, Paine Group.

In early December, 1994, Brad Jarrett, Christian Santelices and I arrived at the Japanese Camp, high in the Río Ascensio valley. From that base, we made carries up the two-hour approach to the foot of the east wall of Cerro Escudo. We spied a vague system of cracks that we hoped would lead us up the 4000-foot wall. On December 17, with two ropes fixed and 500 pounds at the foot of the face, we began a continuous push for the summit. Christian and I shivered the first night as Brad drilled a ladder of rivets to the base of a large roof. Using it as a protection from falling rock and ice, we erected our portaledge under it and crawled in to wait out a 36-hour storm. Rather than the standard single point suspension, our portaledge was anchored from the top and bottom, protecting us from wildly erratic winds and strong updrafts. When the storm abated, we began climbing along a series of thin and discontinuous cracks. Averaging only one pitch a day, we climbed continuously through unsettled weather to the base of an enormous detached flake we dubbed the Red Tower. On Christmas Eve, with our portaledge established beneath the Red Tower, we climbed the right side of the tower. On one of those pitches, Christian crawled out of his aiders, squeezed through a tight crack and found himself inside a 200-foot chimney. Climbing through the dark netherworld, he eventually reached a large ledge at the top of the Red Tower. Two more pitches of moderate aid climbing brought us to a broken ledge system, where we reconstructed our portaledge camp. Wearing rubberized rainpants, paddling jackets and neoprene gloves, we suffered through two pitches in the direct path of a meltwater seep. It was great to retreat to the sanctuary of our portaledge where we had dry clothes, a stereo, books and even a few beers. Two pitches higher, we were at the base of a broken series of overhangs that offered protection. We reestablished our portaledge there. Blue skies the next morning provided perfect conditions for climbing and condor watching. Above the overhangs, Brad started up the hardest pitch of the route. Over the course of ten hours, using beaks, copperheads and shaky pitons, he crossed a number of loose flakes, a very sharp-edged roof and series of loose blocks. A fall on that pitch would have had dire consequences. Finally on January 3, 1995, we were ready for the summit push. Crawling out of the portaledge, we jümared to the top of our rope, where Christian began leading up a hidden corner. There he discovered icy cracks, loose blocks and rotten rock. The next pitch was the same. At 2:30 A.M. on January 4, we stepped over the small cornice that divides the west and east faces of the Escudo. Exhausted after 19 days on the wall, we elected to forgo a visit to the true summit and instead began 4000 feet of rappelling. We arrived 24 hours later on the glacier. (VII, 5.10, A4+.) We have named our route The Dream as tribute to Mugs Stump and as a description of our state of mind after 20 days on the wall.

Chris Breemer

Below is the photo that Chris sent to John Middendorf after their ascent: