History of Portaledge Development 1980-present:

(interview for CAMP, a book about bivouac, 2017)

Alpinist and engineer, John Middendorf, is the portaledge is a natural playground for you ?

I love waking up on a safe perch with huge exposure below, feeling small in the middle of a vertical sea of granite with no easy way down and with lots of challenging climbing above. There is something about the feeling of being committed to a climb that brings out the best in a person. When I started climbing and first saw the walls of Yosemite, I knew the ultimate for me was to climb the tallest cliffs that require spending multiple days and nights on the wall. The portaledge is simply the tool that allows full rest, protection from the elements, and a nice platform to feel safe and appreciate the surroundings.

What is a portaledge ? Could you describe how it works?

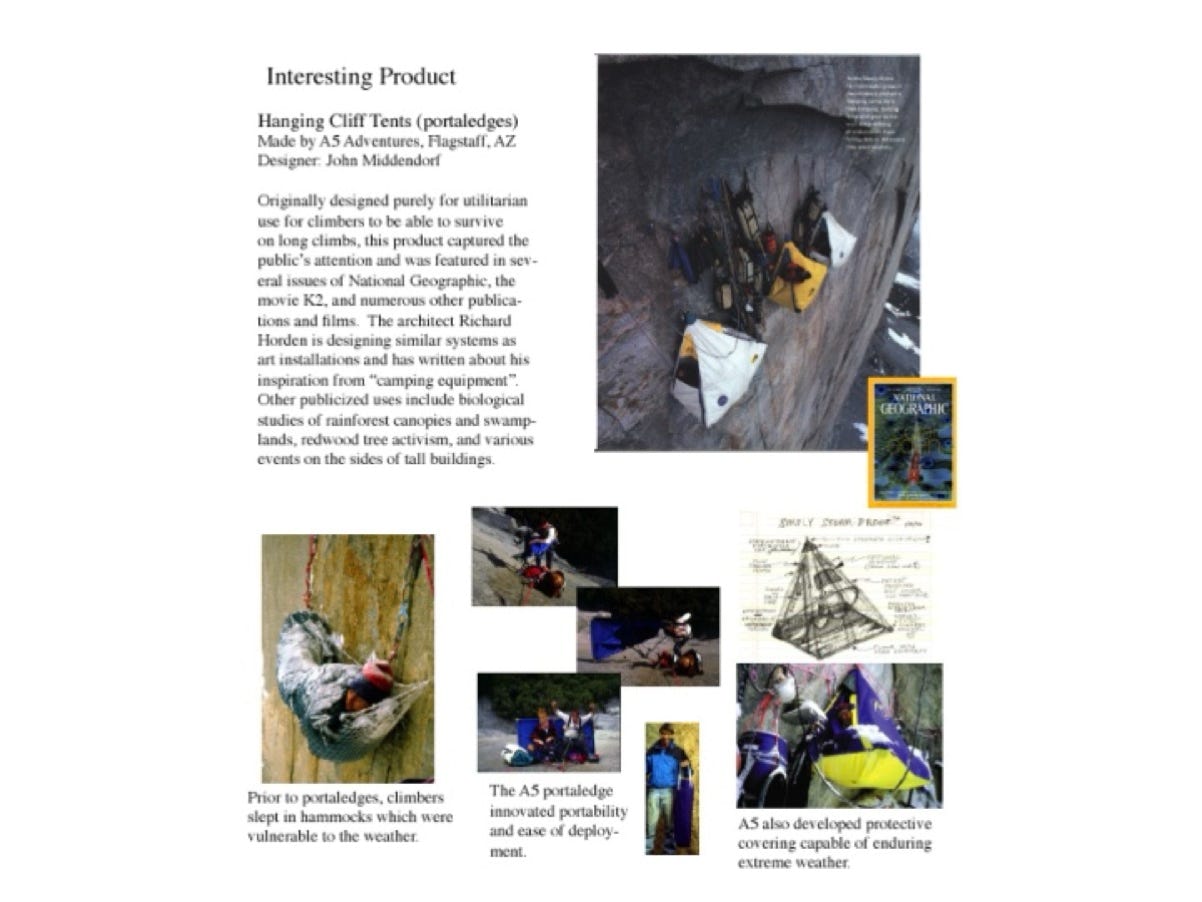

A portaledge is a deployable hanging tent, with a structural frame and fabric bed, which is suspended from a single point. It needs to fold up and be easy to deploy, so it can be carried to remote big walls in a backpack. The single point suspension is essential for climbing because there often aren’t multiple anchors available that are spread out (for a two-point hammock, for example). Sleeping on one is quite comfortable. It's like laying down on a trampoline, sleeping on a portaledge is a similar feeling, one feels cradled, and very secure and stable.

Would you describe your first night on a portaledge ?

I spent quite a few nights on big walls before the portaledge was invented. A lot of the easier routes in Yosemite, like the Nose on El Capitan and the Robbins Route on Half Dome, have natural ledges, so you don’t need a portaledge. But after doing those, I wanted to do some harder routes, with fewer or no natural ledges. In 1984 I teamed up with Alex Lowe and we climbed what was then the fastest ascent of one the longest routes on the SE Face of El Capitain, “Hockalito” (a link up of Hockey Night in Canada--3rd ascent-- and Mescalito). We spent three nights in Gramicci designed portaledges. We were moving too fast to really appreciate the lovely lounge time that can be had in portaledges, but I was amazed at how well one could sleep and be rested for each day using a portaledge and be in top performance for the next full day of challenges.

How was it in the early days before portaledges? Did you spend some nights on big walls before the first portaledge?

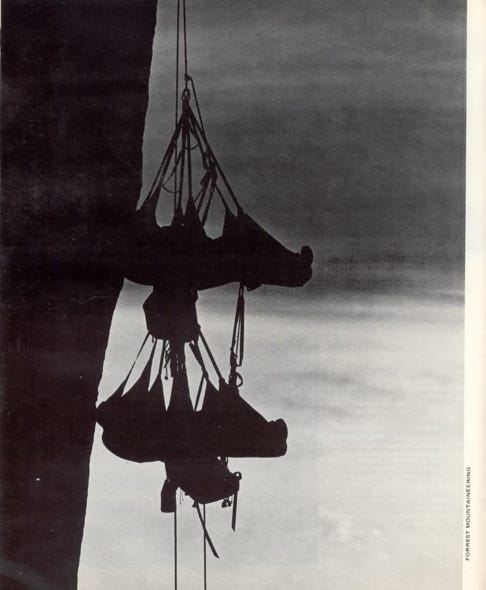

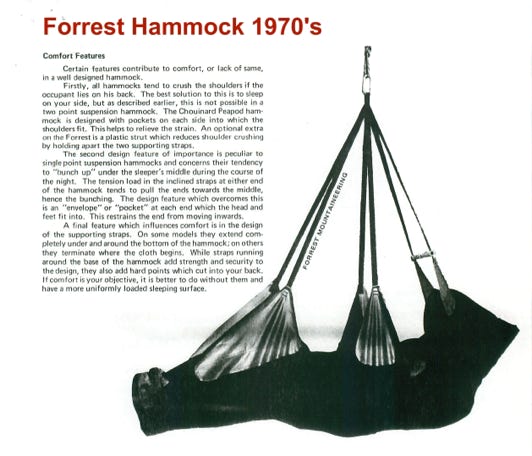

When I started climbing in the late 70's, the only thing commercially available for overnight camping on big walls was the Forrest single point hammock. These were very uncomfortable, and in a storm you were leaning against the cold rock, so you would get very wet because rain generally gathers and flows down walls as a waterfall. And even though the single point hammocks had “spreader bars” to make some room for your shoulders, they were very cramped, and few people could actually get any real sleep in one; suffering was part of the game in those days for big wall climbers so the main issue for hammocks is that they were quite dangerous in storm conditions. Pretty much in those days, if you got hit by a storm while you were on the wall, you were immediately bailing back to the ground, often after enduring a wet, cold, miserable night.

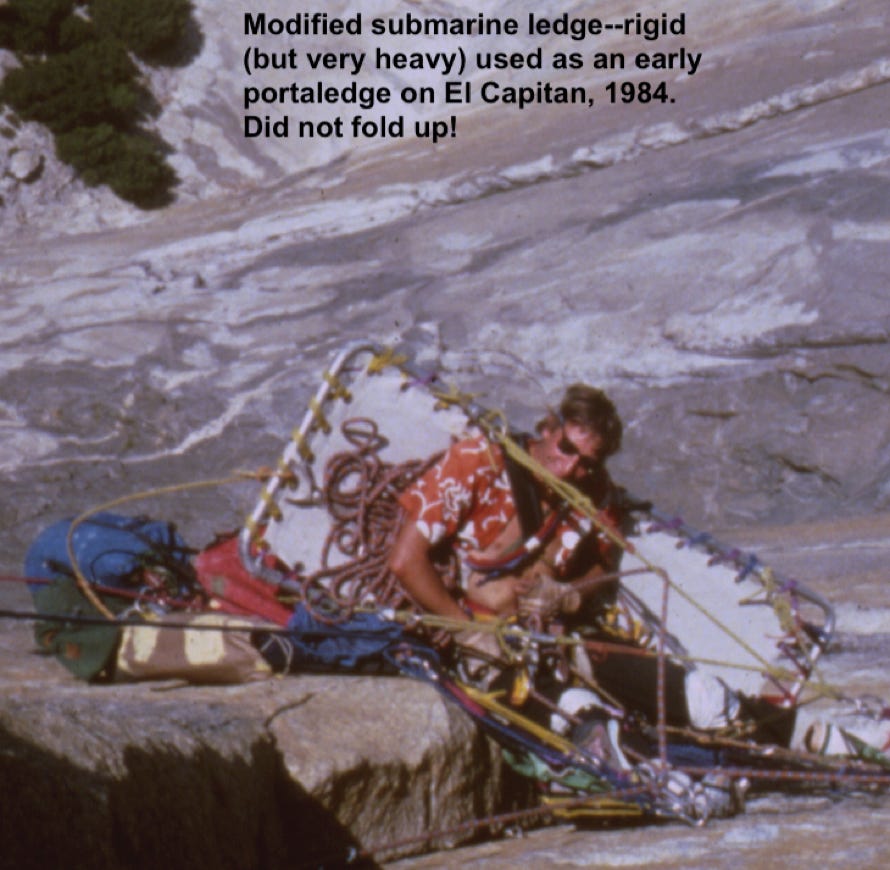

The next step in the evolution was the “submarine” ledge. Navy surplus stores would sometimes sell very heavy tubular steel framed beds that were used as suspended cots on actual military submarines. These would be rigged with slings, laboriously carried up to the base of El Cap (they were much too heavy--about 50 pounds--to carry to routes with longer approaches such as Half Dome), then tossed from the top. The way these flying cots would fly down was terrifying, they would spin, swoop this way and that, and anyone at the base had to run for cover from its wild and unpredictable lethal flight. Then they would get stashed in a secret spot for the next team. Submarine ledges were pretty rare, actually, as the WWII frames were hard to find, but the ones in play were shared and coveted by the big wall aficionados in the Valley in the mid-80’s.

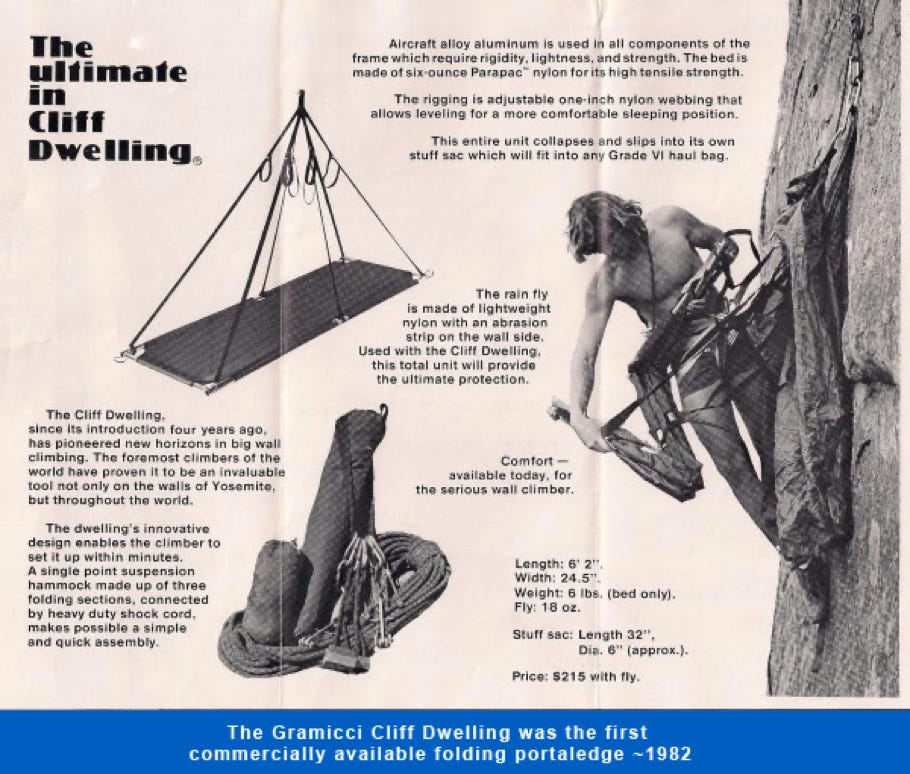

In the early-80’s, a few enterprising folks began manufacturing custom made ledges, brands included Gramicci, Fig, and Frog. These early portaledges could be folded up, but all three of these designs were made of marginal 1” aluminum tubing and had weak corner joints--either pinned or hinged. Non-rigid corners on a portaledge frame led to many nightmares. They worked fine if the wall was perfectly flat, but on big walls the places we camp are sometimes in a corner or on a bulge—in these situations, the stress on the frame causes a portaledge with non-rigid corners to parallelogram out of shape, often causing it to completely collapse, sometimes multiple times in the middle of the night when one was least expecting it. Also the rainflys were made from very lightweight ripstop fabric, the same material generally used on backpacking tents. I found out the hard way that these materials do not stand up to serious conditions possible on big walls.

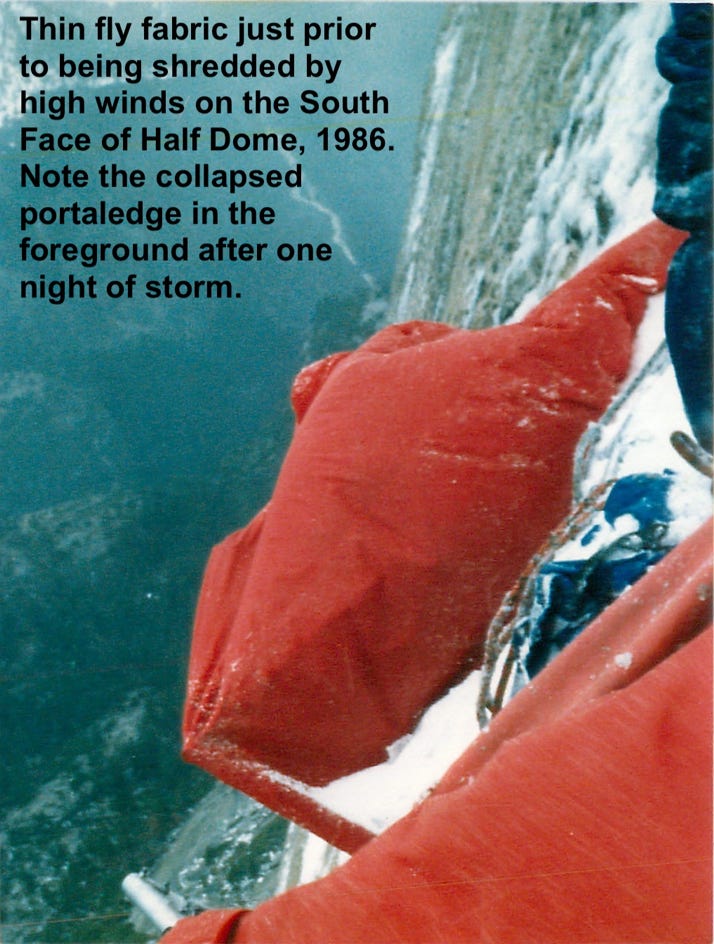

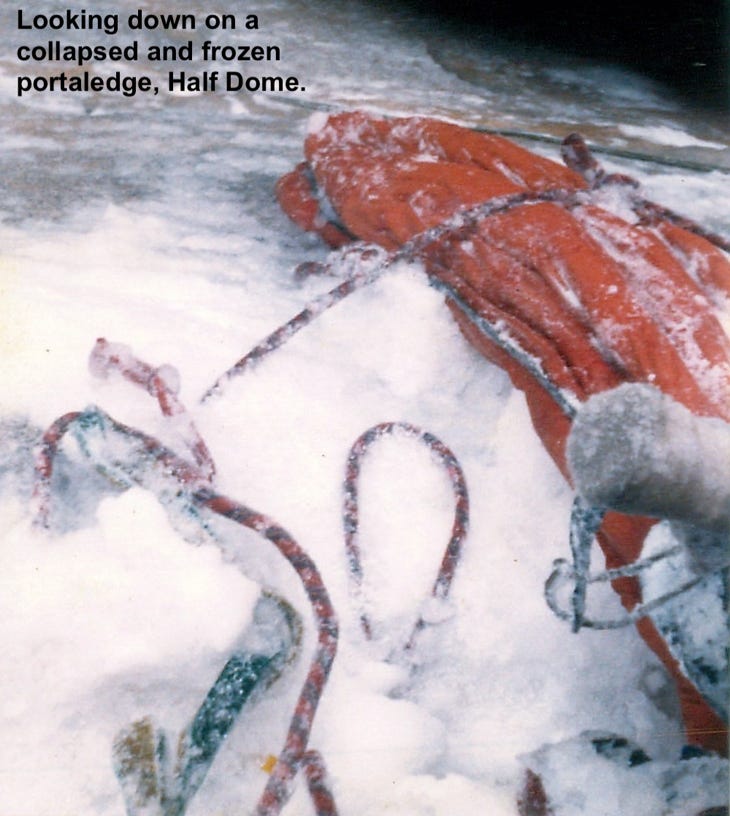

In 1986, a storm tested you and the portaledge severely on the Half-Dome. Could you tell what happened ?

In early wall season, 1986, Steve Bosque, Mike Corbett, and I started up the South Face of Half Dome, a route put up by Warren Harding which had very few repeats. We started in nice weather, but when we were at the “point of no return” (a place on every big wall where it is easier to go up than down), we got hit by one of the worst storms in Yosemite’s recorded history, despite all forecasts predicting nice weather when we started. We all had all the state-of-the-art equipment, but the portaledges of the day were not up for the severity of the storm. The lightweight ripstop flys shredded in the severe winds, and two out of three of our portaledge frames collapsed due to overloading from the ice and snow that piled up on us during the storm. We nearly died of hypothermia the second night, and would certainly have died were we not rescued by a helicopter during a short lull of the third day of the storm.

At that moment, in the storm, while John Middendorf the alpinist badly experiences the weaknesses of the portaledge, is the John Middendorf engineer already thinking about how it should have been designed ? What were the weak points ?

There were two major weak points in the portaledges of 1986: weak, non-rigid frames, and too-light fly covering fabric. People assumed a tent fabric was sufficient for big walls, but the wind and weather on a vertical cliff can be much more severe than on the ground.

In 1982/3 Charles Field designed with a bike builder a chrome-moly steel framed folding portaledge with the first truly rigid corners, and made a dozen or so of the "Fieldware" portaledges. In 1984, my friend and big wall climbing partner Russ “the Fish” Walling, who then had a small business making various sewn climbing gear, took over the Fieldware design, and started producing them in small quantities. I asked him to make me a heavy fly made out of 3.5 ounce Oxford nylon fabric instead of the typical lightweight 1.9 ounce Ripstop fabric. He resisted at first, claiming the packed size would be too massive, but in the end he made me one (it was about the size of a regular football when packed up, but worth ever cubic inch). However, he still continued to make all his production flys out of the lightweight ripstop, despite my pleadings on behalf of other wall climbers who expected the ripstop fabric to hold up in severe storms.

I used the Fieldware/Fish design with my one-off Oxford fly for a few walls, and the advantages of strong rigid corners became apparent. But then I stashed this ledge in Baffin Island in 1986 after a failed attempt on a new route on Mt. Asgard—the next summer the steel ledge was rusted pretty bad (even though my friends Steve Quinlan and Paul then used it for a new route on Asgard), but I realised that steel was not the best material for this kind of expedition climbing. I also noted, and as predicted by engineering deflection calculations, a steel frame flexes more than an aluminium frame for a given strength and design weight (in the case of the original Fieldware design, 7/8" 0.035" 4130 steel tube).

So the engineer inside me started to see a lot of ways the portaledge could be improved, and I began redesigning the portaledge from scratch later that same year in Flagstaff, Arizona, with the help of Barry Ward and Kyle Copeland, two excellent craftsmen with a sewing machine.

In 1986, I already had a mail-order company, A5 Adventures, selling hard-to-find big wall essentials like speedy stitchers, fingerless gloves, hand-cranked tool grinders to sharpen drill bits, big wall spoons, decent battery-powered headlamps (which were very hard to find in those days), bolts, copperheads, hooks, haulbags, and a new forged hammer—all tools necessary for big walls but were unavailable from the mainstream commercial climbing manufacturers. So adding portaledges to the A5 lineup was a natural.

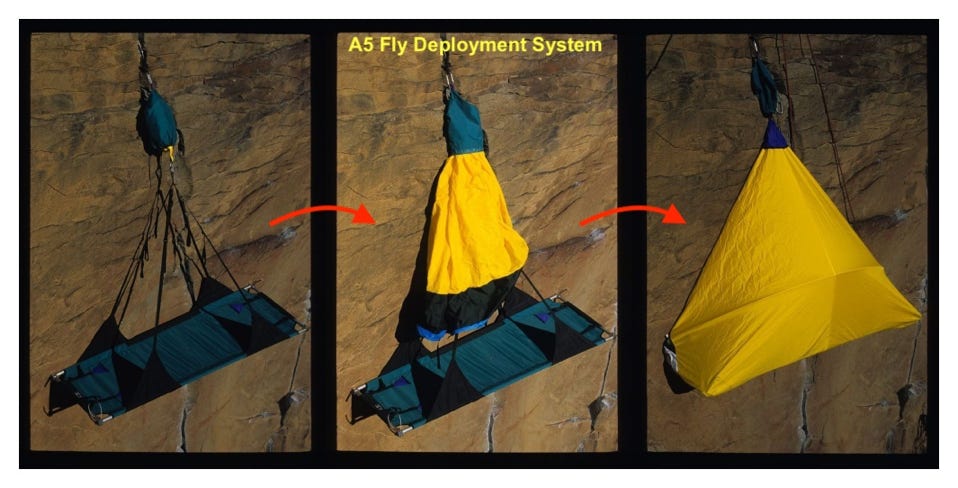

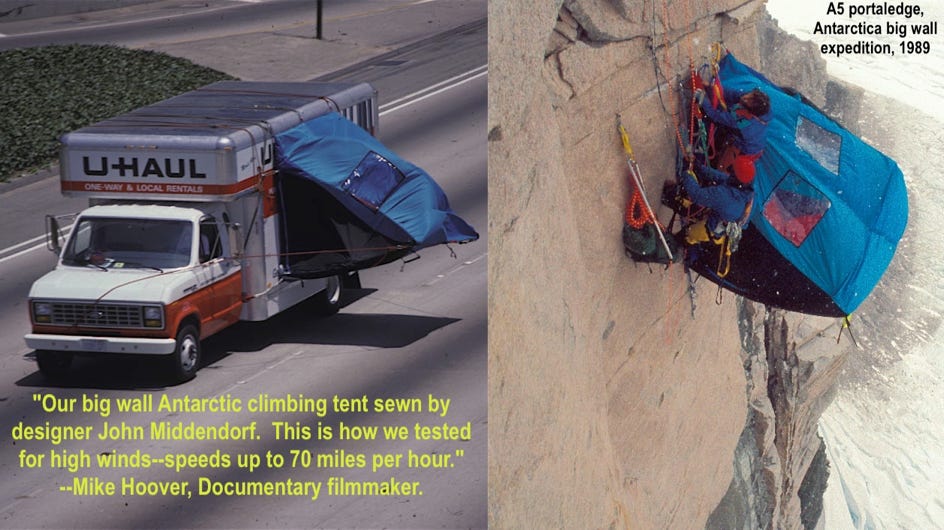

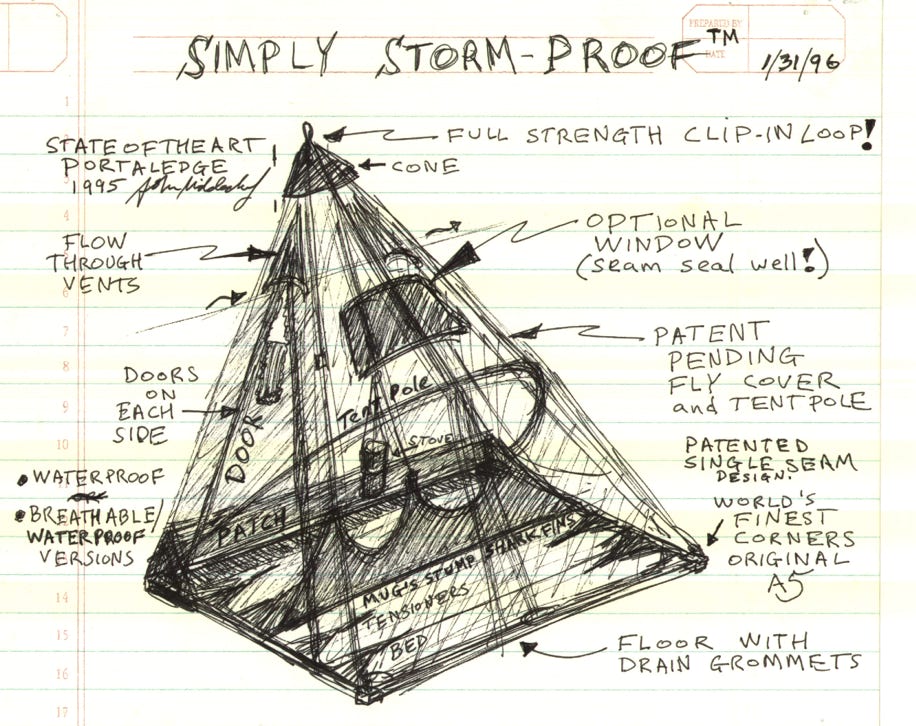

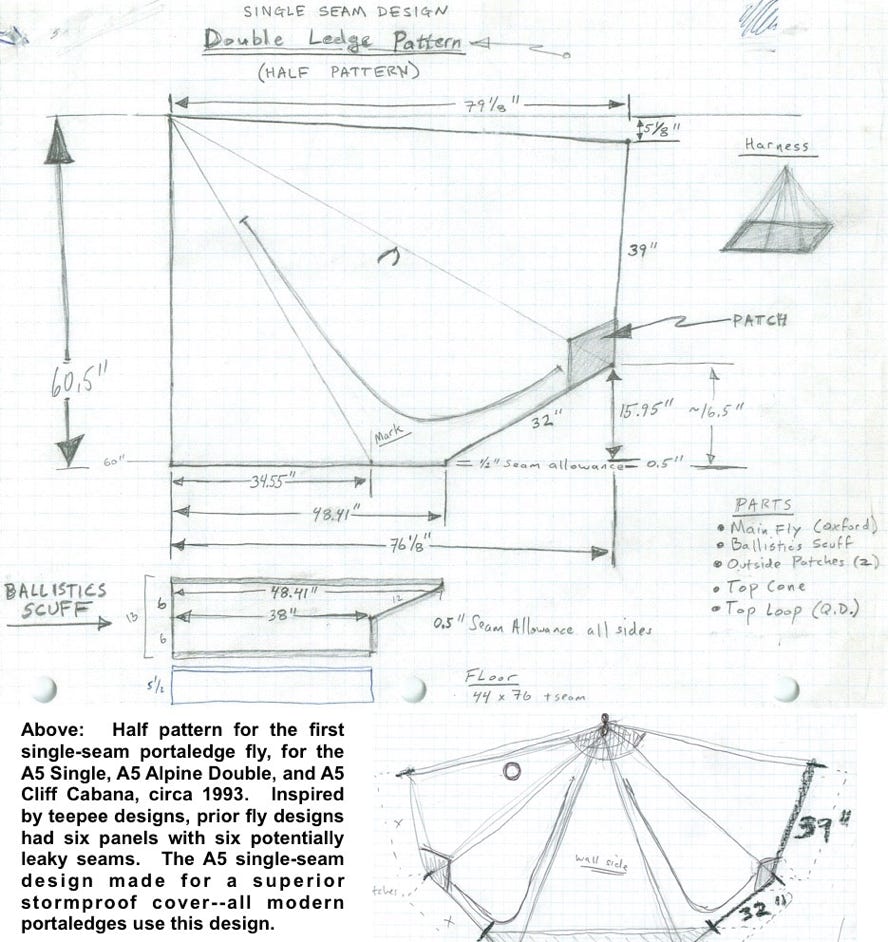

For the fly, we were the first to use the heavier but more robust Oxford fabric in production portaledges, as I absolutely knew the heavier material would be necessary in unexpected big wall condition (in fact, there were a lot of rescues on big walls from climbers with portaledges using the lighter 1.9 ounce tent material in those early days). Now, of course, all portaledge rainflys are made out of the more bombproof Oxford weight waterproof or breathable fabrics. We also innovated the first single-seam portaledge rainfly and the first integrated deployment system which enabled the fly and portaledge to be set up ready for any storm (see "A5 Fly Deployment System" photo).

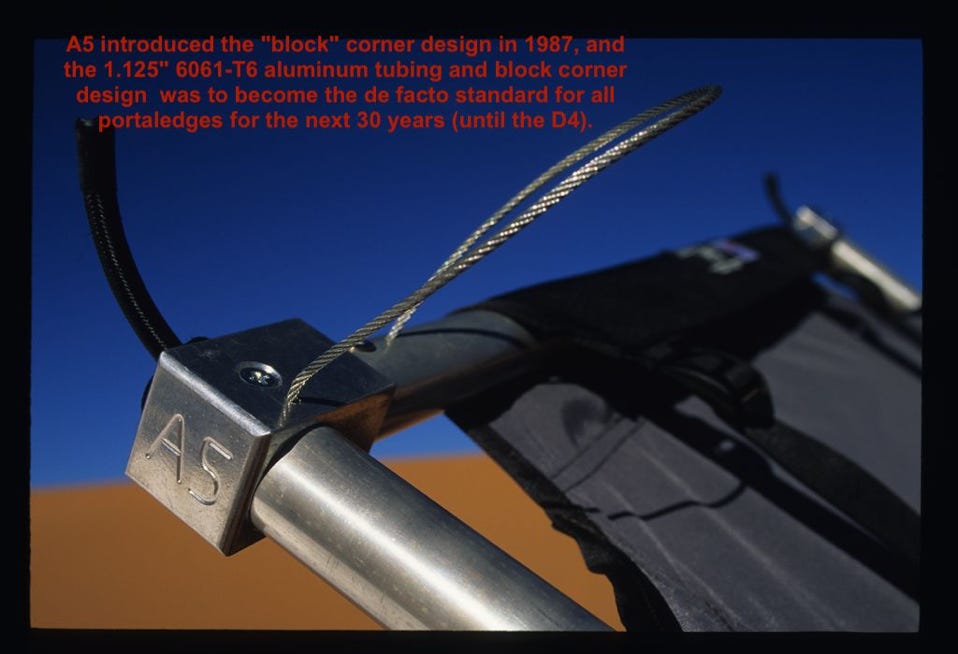

For my early portaledge frame, based on engineering calculations to optimise weight, strength, and rigidity, we used 1 1/8” 0.058" 6061-T6 aluminium tubing (stronger than anything used before), and designed a simple aluminium block corner that was rigid yet made assembly easier. As a bonus, the high quality 1 1/8" aircraft seamless tube was easy to source in small quantities, as it was the same size as the standard hang gliding down tube, which often got bent on bad landings and needed replacement. In fact, Stan Mish called it "hang gliding tubing" when he used a specially designed extendable pole made in the A5 portaledge shop, to establish the first ascent of a Navajo Spire, only accessible via a crafty and scary pole crossing from the summit of a neighbouring spire.

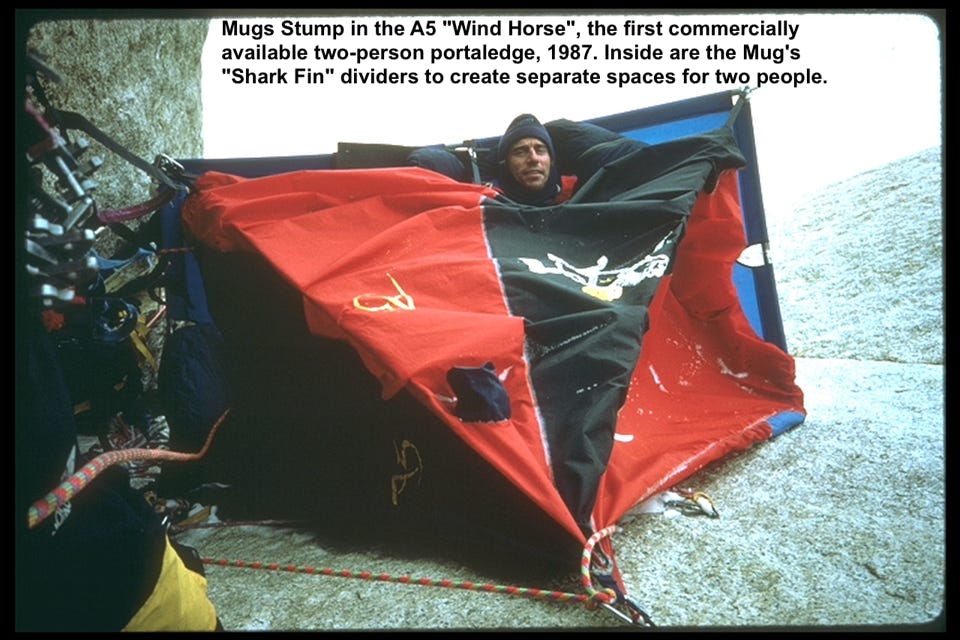

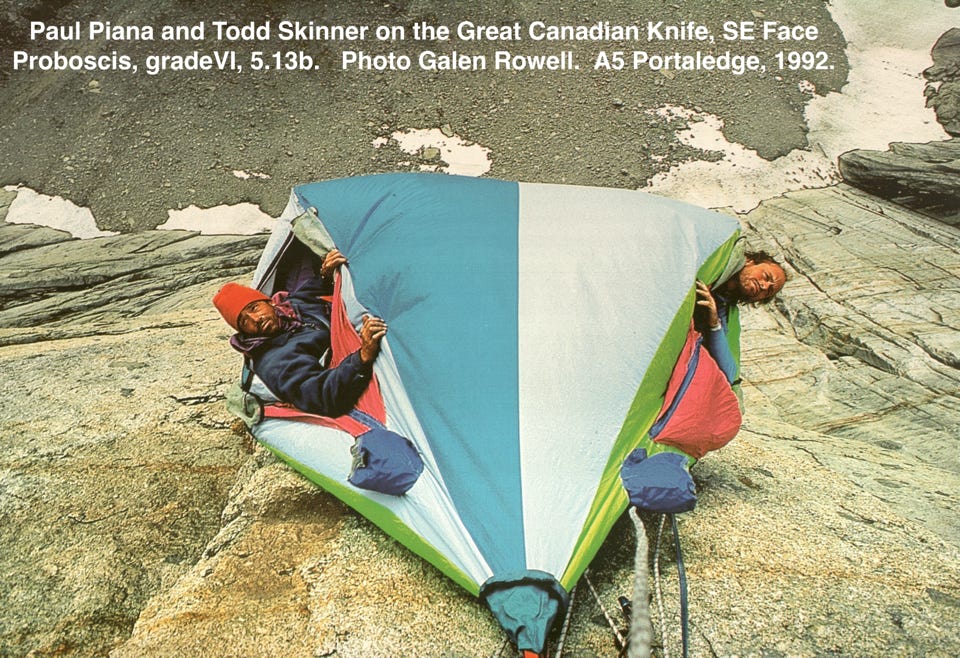

Walt Shipley, another climber and engineer, helped me with the initial two-person folding configuration and joint lengths for the first A5 Double made for Mugs Stump for his breakthrough Alaskan big walls.. The combination of new materials and folding configuration made the A5 deployable frame the strongest and most rigid (less flex) as well as being lighter than prior designs, and this combination of tubing size and block corners has become the standard way nearly all portaledges have been designed for the past 30 years (until the D4 redesign in 2017). The A5 Double was the first commercial two-person portaledge. On expeditions two people in one ledge is much warmer, as well as significant weight savings, so with some ideas from Mug Stump based on his Alaska big wall experiences, we created the first double portaledge with “Shark Fins”, a structural way to divide the portaledge space comfortably for two people, and bed tensioners, another A5 first.

Security, comfort, practicability. When you re-invented the portaledge (the first time), what was the priority ?

Lightweight, small packed size, easy to deploy, and stormproof. The A5 portaledges were the first truly stormproof portaledges ever, and really precipitated a huge boom in big wall standards around the world in the late 1980’s and 1990’s. So many big walls were climbed for the first time in this era without recourse to extensive fixed ropes, which had been the norm in places like Patagonia and the Himalaya before this time, and they all used A5 portaledges. It was the first time big wall climbers could go up in any conditions and be assured of survival even in the worst Himalayan storms.

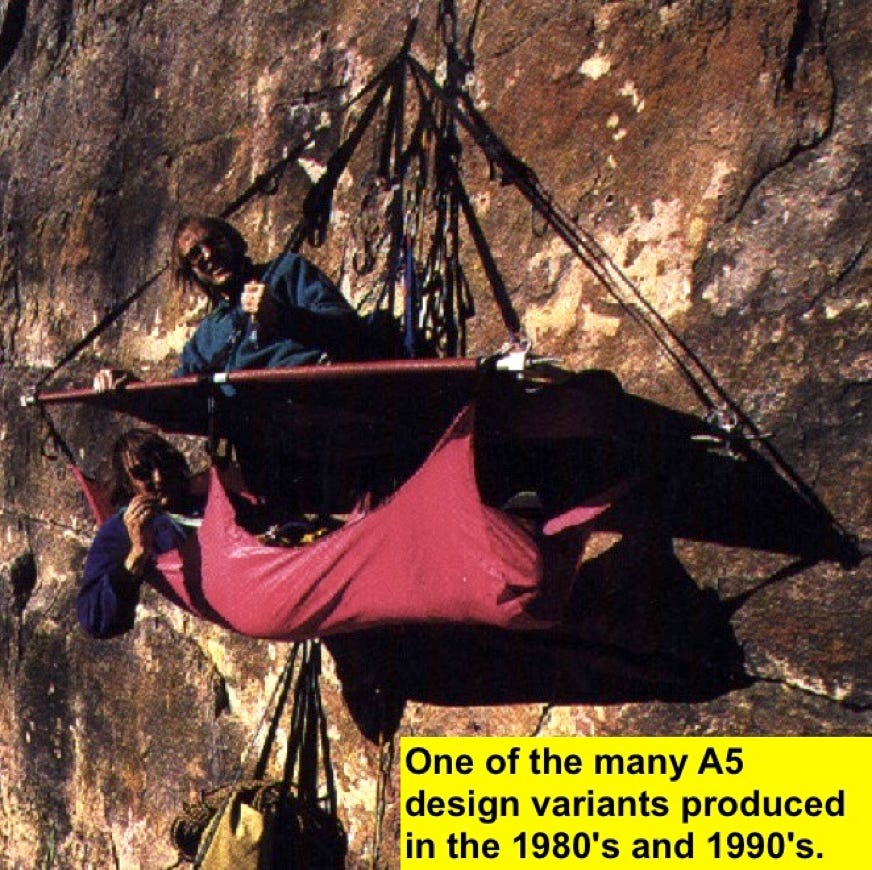

During the 10 year period from 1987-1997, we innovated pretty much every feature you see on portaledges made today, including the shark fin divider, bed tensioners (making assembly and disassembly easier), cam buckle suspension (the only things that work in icy conditions!), single seam fly (reducing leak spots—prior designs used six panels and seams to make the fly), ready-to-deploy fly system (eliminating the nightmare of having to exit the ledge at the beginning of a storm), and many other features now the de facto standard. Ultimately, we created the first truly stormproof portaledge, one that could withstand even the fiercest Himalayan storms. The A5 portaledges have stood the test of time, and the modern commercial offerings are direct clones of the A5 engineered design.

Do you remember the first time you brought the portaledge designed by A5 Adventures on a wall ? Where was it and was it conclusive ?

I personally tested every iteration of the A5 design in those years on big walls, and after each wall, would come up with new ideas and features. I would say a big wall in 1991 was when I knew we had really come up with the first truly stormproof design—Steve Quinlan and I climbed the third ascent of Tribal Rite on El Capitan, we were both pressed for time, so started in a storm with the logic that it would soon clear, but it did not clear, every day for the next 7 days we were hit by storms. But with the new technology, we were able to get decent rest in the lulls between storms. I knew then that the bivouac technology would never again be a limiting factor for big wall climbs.

What other portaledge designs did you produce?

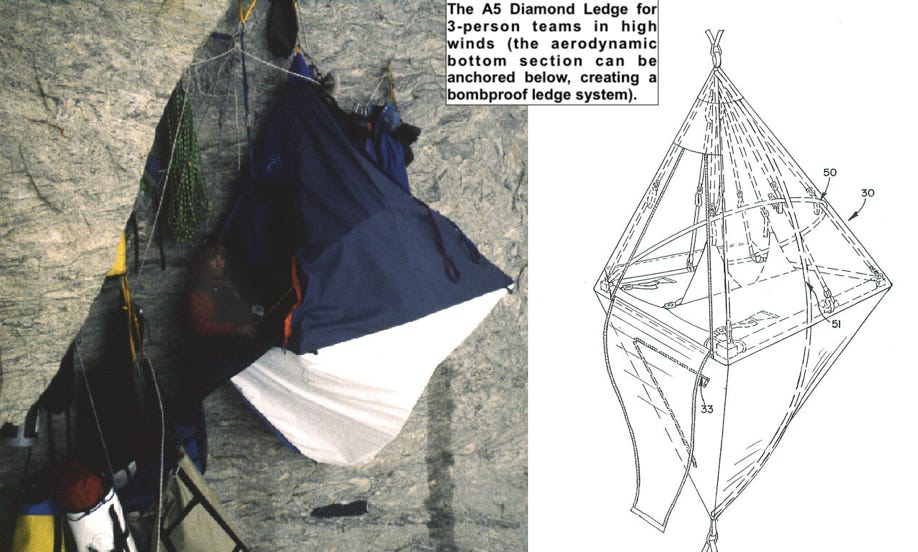

We probably made over 20 variant portaledge designs in those years. We also made a lot of custom portaledges, like the six pound ultra-light titanium single ledge system (72" x 24", packed size: 25" x 5") for Catherine Destivelle, which she used on a historic solo first ascent on the Dru, and the three-person A5 Diamond Portaledge, where the third person sleeps in a suspended (and comfortable) six-point hammock underneath the ledge. I designed and made the first prototype of the Diamond Ledge for a planned first ascent of the East Face of Cerro Torre, where extremely high winds were expected as the ledge could be structurally tensioned from above and below, but that expedition failed (though we did climb the Maestri route in 14 hours), so the A5 Diamond Ledge was first used for the historic first ascent of the East Face of Escudo by a three-person team. The Escudo ascent was the first major "alpine-style" big wall ascent in Patagonia (the ascent did not involve extensive fixed ropes to the ground), and established a new paradigm in Grade VII Patagonia ascents. We came up with a lot of other one, two, and three person designs made back then, but the A5 Alpine Double was the ledge of choice--the best compromise between weight, packed size, and simplicity--perfect for survival and comfort on the most extreme walls on Earth.

More personally, what is and still remains your best vertical camp experience on a Big Wall ?

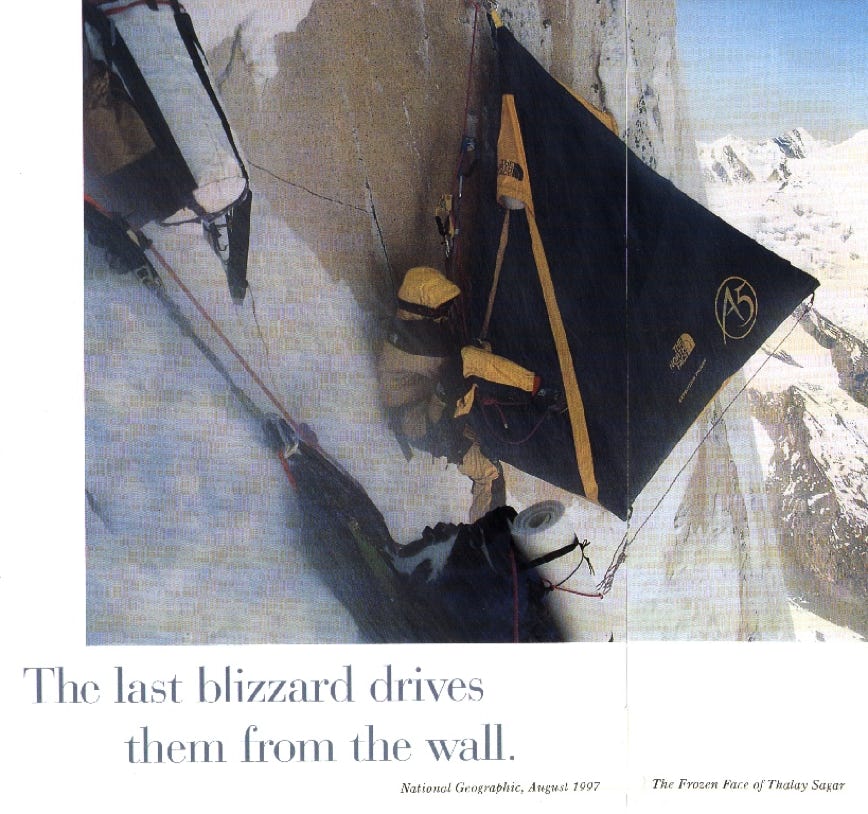

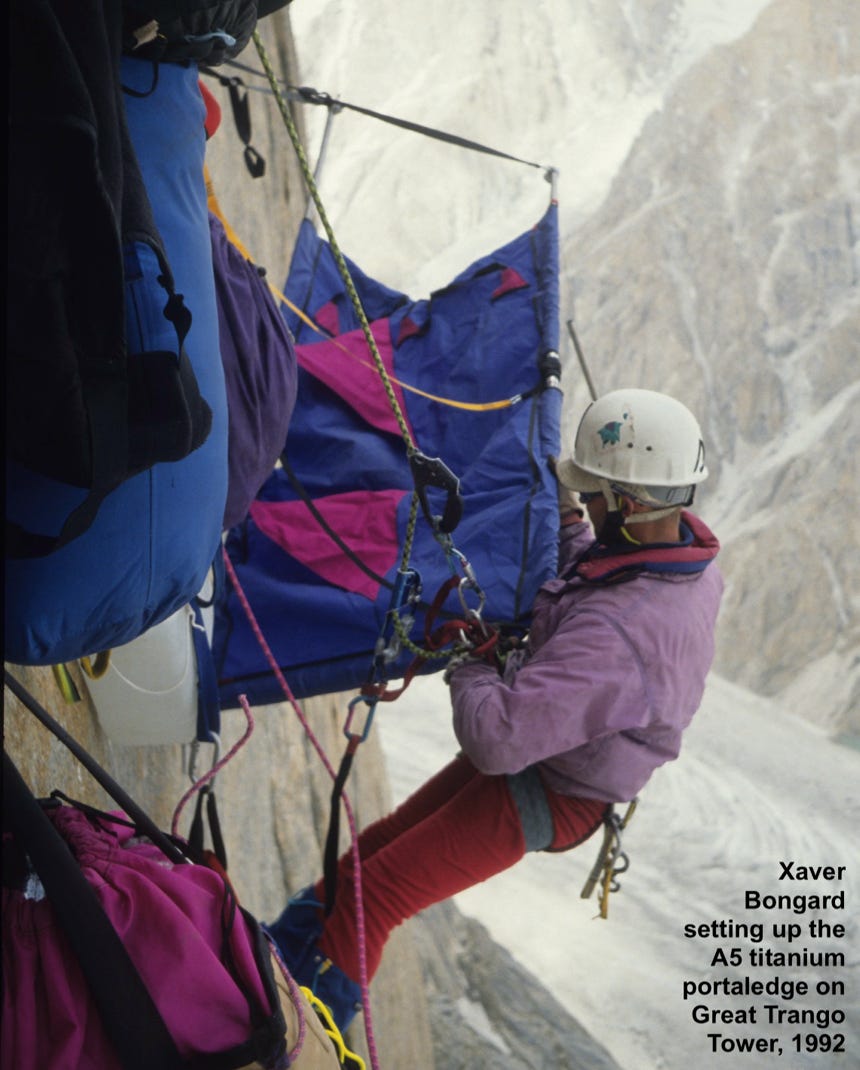

So many fit this description! For me, it was about the partner. I had incredible times climbing with Walt Shipley, Steve Quinlan, Werner Braun, Derek Hersey, Mugs Stump, and Xaver Bongard to name a few. Probably the time Xaver and I withstood a three day storm at 19,500 feet on Great Trango Tower. The winds, which on a wall come straight up, was lifting the entire ledge with us in it, and crashing down. For that route I had designed a super lightweight titanium frame, and I kept wondering if I had done all the calculations correct. But it withstood. Seeing clear sky for the first time in days, knowing we were blessed with a weather window for the summit, was magic.

In 1997, The North Face bought A5 Adventures. Then the design went to ACE, and eventually your designs went Black Diamond in 2005. How the portaledge has progressed in these past 20 years ?

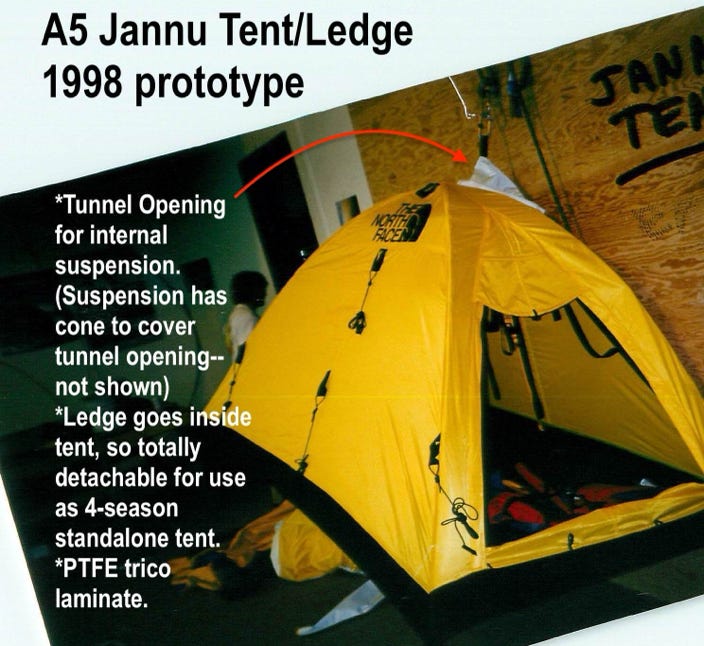

Frankly, not much has changed from the solid 1997 A5 design, though I was able to make a few improvements the two years I worked as Senior Product Manager of the A5 Division at North Face. The reason I sold A5 was to have the greater design resources of a large company, and at North Face we were able to offer such features at factory-taped seams and customised fabrics, such as an improved PTFE breathable fabrics for expeditions to cold and dry regions, and lighter but tougher Uretek fabrics (compared to the ballistics fabric we had been using) for the abrasion reinforcements. North Face had an outstanding fabrics testing department, I was in there a lot!, as well as making frequent trips to California manufacturing facilities to ensure high quality during the transfer of new production of my design.

Since then, there really have been no significant design innovations in portaledges, in my opinion. There have probably been at least three dozen different versions of the A5 design made by a number of smaller businesses, and the main suppliers, Black Diamond and Metolius, use the same basic A5 aluminium tube and block corner construction, with no significant improvements in the past 20 years. Perhaps the Metolius top metal clip-in (instead of a webbing attachment) might be considered an advance (or perhaps a convenience at the expense of weight), but all other aspects of the modern portaledges are essentially A5 features, with the exception of the Fieldware/Fish, which hasn't changed much since 1986 (for example, they still use the old 6-seam fly design!). There’s a few new cool details I see from time to time on the mainstream portaledges, but on the flip side, these companies have added a lot of unnecessary weight like the spreader bar. And nobody is really improving on weight and what might be the most important aspect for mobility--the packed size.

So, after 20 years, you decided to take some action?

In 2016, I met a friend on a family camping/climbing trip to Arapiles, who knew of the lightweight portaledge designs we used to make. He was really psyched on big wall climbing, and lamented on the fact that only big heavy and cumbersome portaledges were available. His interest and enthusiasm brought my mind back to portaledge design. My first step was to redesign the frame to eliminate the need for a spreader bar, then one thing led to another, and I have since re-invented a whole new portaledge design with a number of significant innovations that create a lighter, stronger, more compact (when packed), and easier deployable full size portaledge. The prototypes of my new design have already been out in the field with top climbers, who have all stated that this new design “changes the game” due to its lightness, function, and packed size.

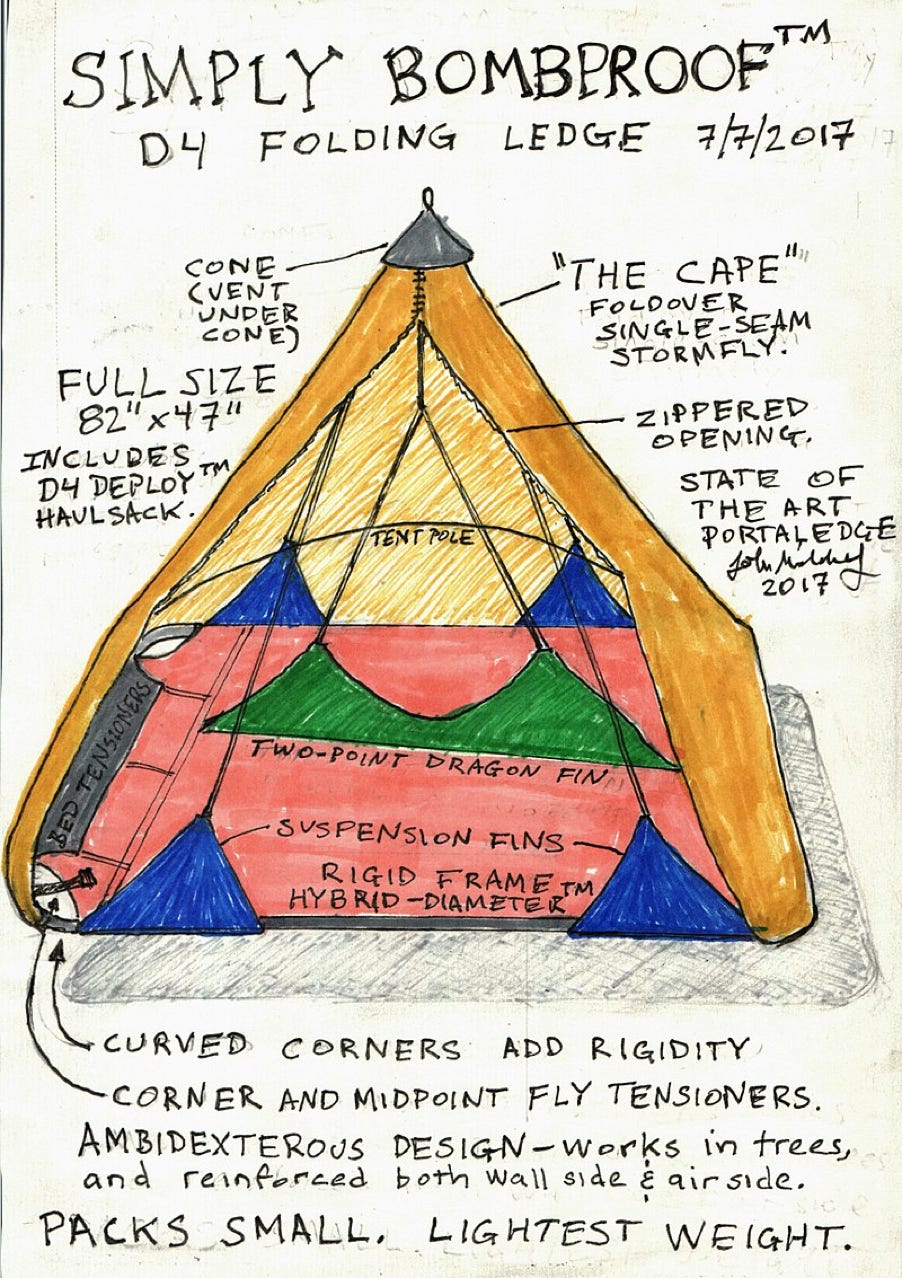

In 2017 you launched the D4 Portaledge Kickstarter, "The Portaledge Re-invented". Could you tell us more about it ?

The D4 Portaledge is really the new paradigm for larger, full size ledges (82" x 47"). I needed some funding to keep my ideas going, so the Kickstarter was the perfect way to gauge support--there was! The Kickstarter was fully funded within 72 hours. Of course, it is way easier to create a one-off prototype than to go into production, so then we got to work--and after six months of extensive testing and development, we started shipping the D4 portaledge to Kickstarter supporters. The lightest version of the D4 comes in at 15.5 lbs, almost half the weight of the BD Cliff Cabana, and packs about half the size as well. The D4 portaledge is full-size like the Cliff Cabana, but is lighter, way stronger and more rigid, thanks to the design (I used CAD tools--Autodesk Inventor and Fusion-- to analyse and optimise the stress and strain characteristics of the new hybrid-diameter, curved corner tube ledge design.) Then I personally tested the new portaledge over three days and nights on a big wall at Mt. Buffalo, Australia, with Simon Mentz, my first wall in 20 years! (Footnote: we completed all Kickstarter orders on time in 2017).

What exactly are the innovations of the new portaledge?

Three simple concepts are behind the primary new innovation, all combined perfectly to create a better design: The first new concept is the "Hybrid Diameter Tube" frame design. I initially conceived of using two different diameter tubes--using a larger, different diameter tube where there is the most stress--while advising a startup in Squamish (I have advised a lot of companies in the past 20 years, whenever asked, hence the many homemade and commercial versions of the A5 design). The goal was to re-engineer the frame for a larger size ledge so that the spreader bar concept was superfluous; BD and Metolius both use a spreader bar in their design, but they are abhorred by climbers, as it often digs into ones back when lying down, and makes assembly more difficult. The A5 ledges never needed spreader bars, but the tubing of each version was specifically designed for both the load and the size. The problem for these other companies is they made the platform size bigger, did not re-engineer the tubing (they used the same tubing size as the smaller A5), so they had to add a heavy spreader bar to prevent the inevitable flex that this design method produced. They really should have re-designed the frame from scratch.

After discovering the advantages of the hybrid-diameter tube concept (new options for the joiners for example), I started looking at more compact folding configurations. I had an idea for a curved corner portaledge way back in the 80's, but back then the main priority was to create and refine many other features that all were needed to create something truly stormproof, and my block corners were tried and true at the time. A few years ago, I had been playing with bending tubes for some architectural projects, and realised that curved tubing would work for a compact folding portaledge if there was some new clever geometry involved. A critical design constraint of portaledges, of course, is the packed size. When I first saw the packed BD Cliff Cabana last year, when a climber was walking down from El Capitan, I couldn't believe the packed size! The original A5 Cliff Cabana design was a 10-piece frame design, so the portaledge folded into a package about 29" high. But BD decided to change it to a 6-piece frame (same as its smaller cousin, the A5 Alpine Double, currently being made by Runout Customs), and this resulted in a packed size of over 4 feet--much too big to be reasonably carried on a difficult big wall approach (in addition, the BD Cliff Cabana weighs nearly 30 pounds with the added spreader bar and other added "features").

The new D4 frame is an 8-piece design--it actually took quite a bit of work to discover the new geometry. So the three things: hybrid diameter tubes, curved corners, and a new folding geometry all combine to make the D4 the most strongest, lightest, most compact folding full-size ledge ever. This has made a big difference in how and when people use portaledges--for example Robbie Brown and team recently took a D4 for a one-day speed ascent, because the ledge was so compact to carry, and useful for relaxing at belays (normally one day speed ascents are quite minimal in terms of big wall equipment).

The D4 portaledge is also being widely adopted by tree campers--this hybrid diameter rigid frame is really the first portaledge suitable for tree camping--prior portaledge designs do not have a reinforced centre tube and thus would flex wildly when set up in a tree, because all the load is at a single spot in the centre of the frame--the worst possible loading situation for a portaledge--the D4 is super solid in a tree-loading situation (see photo).

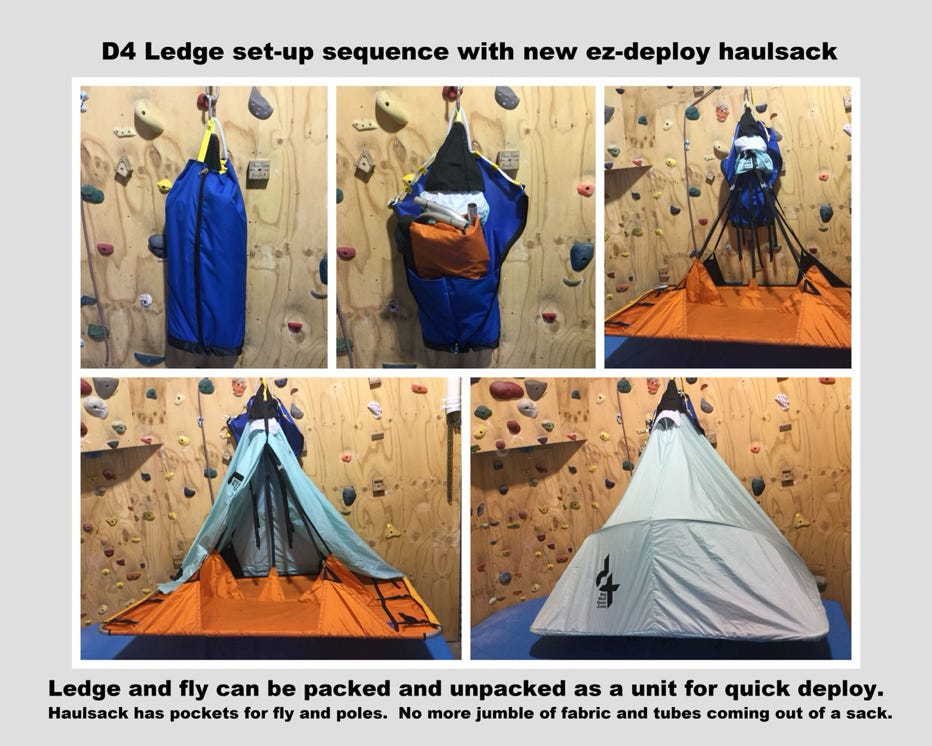

During the Kickstarter process, we also innovated a lot of other cool new concepts for portaledges which will likely become industry standards, such as a zippered haulsack that makes deployment and pack up much more straightforward and orderly, and many new fly features, including a tensioning system, and a single zippered opening on the main seam which allows full venting of the ledge after a storm, while offering the highest level of convenience and access in and out of the ledge. The D4 is the easiest to use ledge system, and just like in the 80's and 90's with the A5 design, when there was a huge boom in standards with the first truly stormproof ledges, this new design will expand climber's potential objectives, being lighter, more compact, and much more versatile.

What still needs to be improved to get the perfect portaledge ?

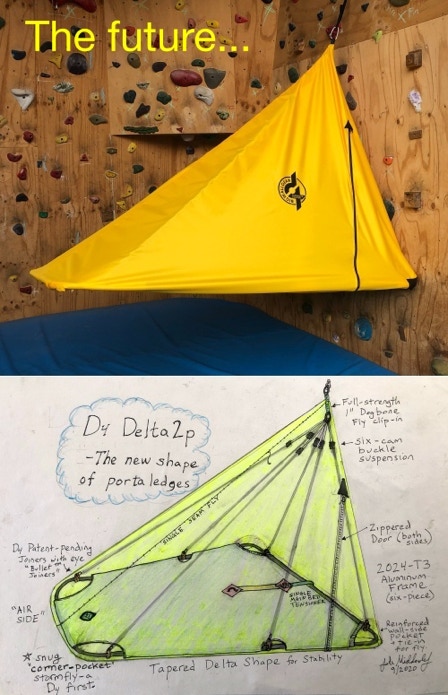

For a long time, I have worked on self-assembling frame systems which fully deploy with gravity--take it out of the bag and it self assembles--and have filed some patents on these unique designs. But there is a trade off between weight and deployability. I believe my new D4 design with rounded curved tubing corners and the many other new innovations will become the state-of-the-art for many years. It’s also the first ledge design that will be well adapted to a super light carbon fibre version, as the curved corners distribute stresses as well as offering more frame rigidity (block corners create higher compressive stresses on the corners). Basically, lighter and more compact folding ledges (that still enable climbers to survive serious storms) are the future, and the D4 sets a new standard in these respects.

It's important to note that now, just as back in the A5 days, the recent evolution has really been a community effort--I have brought some new ideas to the table, but many talented people have been involved with the refinement and product testing of the new design. That is probably my greatest strength as a portaledge designer, to reach out and incorporate a collaborative effort among the top climbers during the design process--it has been a very open process (see the Kickstarter updates), very distinct from how the big companies develop new products, and the end result is a stronger, lighter, more compact tool that will help climbers further their climbing dreams and objectives. As a bonus in the coming years, it will be fun to see the curved corner design become ubiquitous in images of portaledges often seen in the mainstream media!

John, for those who will never sleep on a big wall, could you tell how magic it is ?

Just sleeping outside in a remote place is half of the magic. The other half is the way the wall energises, just sleeping in the middle of a sea of granite, looking forward to seeing the sun peek out from around another part of the wall because there’s a full day of fun ahead. They are really quite comfortable too. One feels quite cradled by the experience.

--John Middendorf (interview for CAMP, a book about bivouac, by Luc Gesell, 2017)

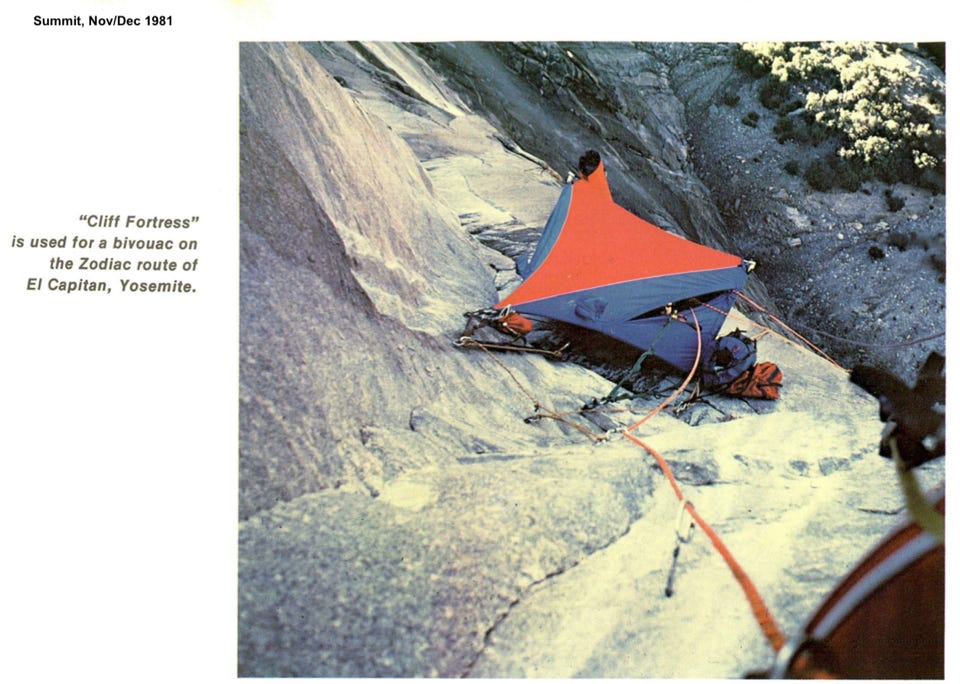

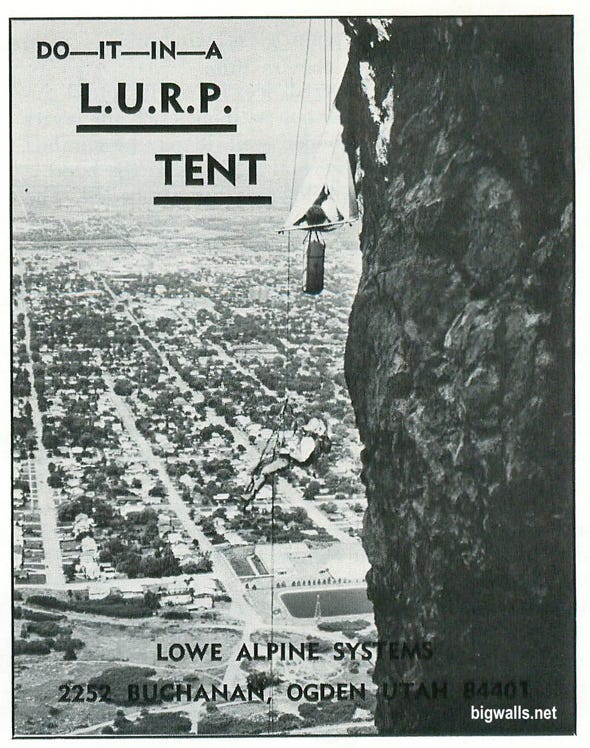

Greg Lowe designed his LURP tent for his 1972 winter Half Dome ascent, and it was used for other cutting edge climbs, but was never made in production.